detour 309_via Counterimaginary 2

Trash Monsters

By: Dulmini Perera, Eugenio Tisselli, Jonathan Jae-an Crisman, Karl Beelen, Lana Judeh and Omnia Khalil

Source/Link:

K LAB, 2020

Text:*

* drafted shortly after completing our workshop; see detour 306

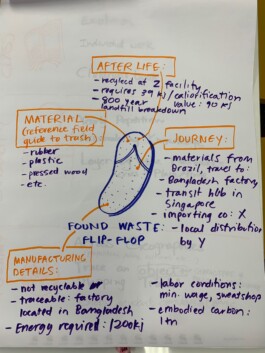

Trash Monsters is a class syllabus that aims to create a reading of the city through its landfills in order to unpack social and materialist relationships through specific trash objects chosen by students. The class is designed to have three stages in the course of one semester: pre-expedition preparation, expedition, and post-expedition. Expedition is a term that refers to a journey that the students will undertake by visiting the city’s landfill sites and trace a number of chosen objects. Based on these trash objects, which will be classified according to a sort of demonology or—better yet—monster-ology, the students will be able to assess the capitalist flows in the city by unpacking relationships of production and analyzing the social, political, economic, and environmental networks that are at play. Moreover, students will carry out an intersectional study of the city workers who are involved in the different processes of collecting and classifying trash, as well as the citizens who (re)produce trash in their everyday lives. By layering the different agents involved in the processes related to trash, students will be able to identify the monsters at play and their positions and relations of power.

The monster-based classification of trash objects is designed as both a critical and fun conceptual tool for understanding the implications of trash, as well as our own relationship in its production and our vulnerability in face of its effects. We have thought about several monsters that may be embodied in each trash object. For example, the monster of non-recyclability will be used by students to classify trash objects that are non-recyclable, or the toxic monster will be embodied in trash objects that are polluting or harmful to human health, and so on. Throughout the class, monsters will be identified by specific icons, which can be modified and adapted in order to respond to different cultural contexts.

In the designed syllabus, the first stage, pre-expedition preparation, will include the study of a table of trash characteristics that can be directly related to the different monsters, in addition to readings about infrastructure. The syllabus will also include a review of art projects that may inspire the work of collecting trash monsters, such as Mierle Landerman Ukeles’s Touch sanitation, Jenny Odell’s Bureau of suspended objects, or Ubiquitous Trash by the TRES art collective.

In the second stage, the expedition itself, the students will embark on a journey that will take them through the city’s landfills. There, the students will perform different tasks. They will have to choose trash objects in order to analyze and classify them according to the monster-ology. This process will be assisted by a smartphone app, which will allow them to record the collected objects using georeferenced images and sound recordings similar to the ojoVoz project. In addition to taking photos of trash objects, recording voice messages explaining the possible narratives linked to those objects, and mapping them using the smartphone’s GPS, the students may also interview workers at city dumps, as well as residents of the city. Each student will be asked to collect 4–5 objects, which, again with the help of the app, will be classified according to the monster categories. Thanks to the collaborative work of 10–20 students, a categorized multimedia map of trash monsters lurking in the city will be created.

The trash monster app will allow students to navigate their own research of the trash site and map it using multiple criteria. Two kinds of data are seen as vital in the production of maps that relate to the questions of waste injustice, meaning the disconnection between trash production and trash dumping. 1) The hard data components, or what we could define as quantitative data, which can potentially be aggregated into large data sets that can be gathered through disembodied forms: for instance, labels, chemical compositions, barcodes, etc. 2) the soft (embodied) data that can only be accessed by taking the app for a walk across the landfill. Consequently, the trash monster app will use two types of interfaces. The first one is an audiovisual mapping interface linked to the predefined monster-ology used to categorize the physical and hard qualities of a trash item. Thus, this interface will help students create a counter-cartography in which different trash monsters are located within the city. The second interface will be used to map the local narratives and stories related to the production, collection, and management of trash. These narratives, in turn, will be recorded as soft layers of information. The goal is to teach students how to identify and confront trash monsters and reflect on their origins and effects. The counter-cartographic visualization of the monsters will allow the students to see the agency of all the trash-related stories, as played out within a local site, without losing track of their inherent links to global capital and questions of global asymmetries.

The post-expedition stage will include the analysis of the collectively produced map with trash monsters and trash-related stories. This analysis will include three different vectors. The first one will take place on a class scale, where students will be invited to write a children’s book that narrates stories about the trash monsters in their city and will introduce the connections between location and materials in an accessible way. Within this first vector, students may additionally pick one particular trash object for a more in-depth translocal research. The second vector will be connected to temporality, considering that the class may be repeated over time. With the help of the app, the collaborative counter-topographies of trash may accumulate temporal layers with new trash items and stories. The aim of such layering is to favor a more lasting involvement, as well as a long-term understanding of a city and its intersection with capitalist relationships and networks. The third vector will be a translocal one, given that the trash monsters syllabus will be repeated in different geographies. This translocal understanding of trash will allow students and researchers to unpack the material networks and flows of the industrial system that produces waste. The trash monster app will include the counter-mapping exercises, replicated globally. Such global case studies will allow the data sets to grow and will help to identify and make connections to similar trash monsters appearing in separate geolocations. Through group discussions, these separate geolocations can be connected by means of the material aspects of corporations, capital, and global flows. How can the same monsters exist in completely different localities? And what can the monsters tell us about global capital? What do the qualitative data, such as voices and narratives, tell us about how specific localities fight, or come to terms with, the trash monsters?

Finally, our team believes that this educational project directly addresses the issue of climate change in cities by grounding it in the misleading banality and exasperating ubiquity of trash. The project aims to reveal our participation in the production of trash in one of its concluding questions, which deals with the possibility of using the monster metaphor as a way of reflecting on how we, as consumers and producers of waste in a capitalist environment, are often involved in a rather monstrous behavior. Are we the real trash monsters?

Back to Text